IDOE hopes data will inspire changes to decrease absenteeism

State education officials hope laying out all the data on student absences will help better paint the picture convincing schools, parents, and local communities to work to combat chronic absenteeism.

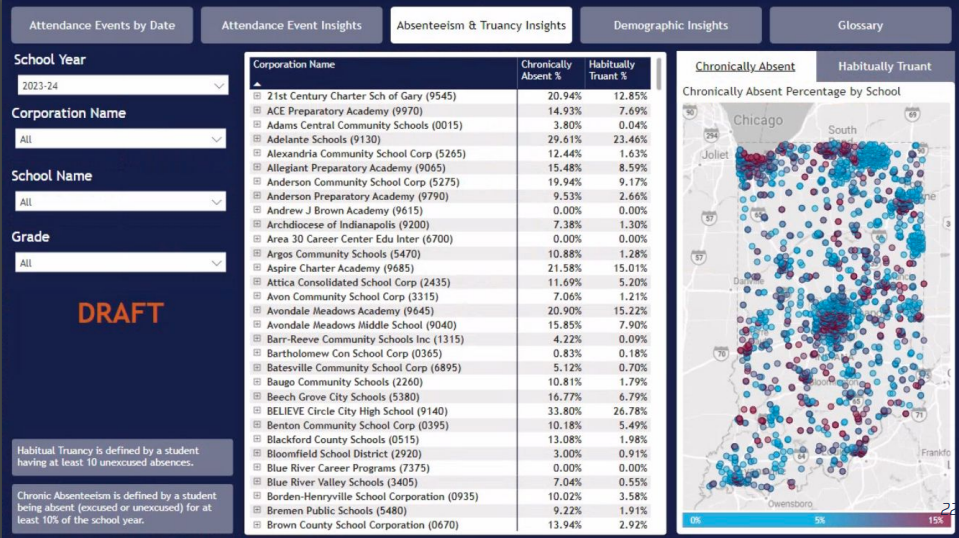

We previewed for you in our last issue that the Indiana Department of Education is launching an attendance dashboard. The department first launched the dashboard for just schools late last month but plans to post a public dashboard with much of the same data in the coming weeks.

The dashboard will include local data on excused and unexcused absences by school district, which can then be broken down by school building, grade level and demographic information. Viewers can also look at a map of the state visually showcasing the big picture of how different schools compare across the state. Data can be viewed by week, showing which specific times in the year students are missing school.

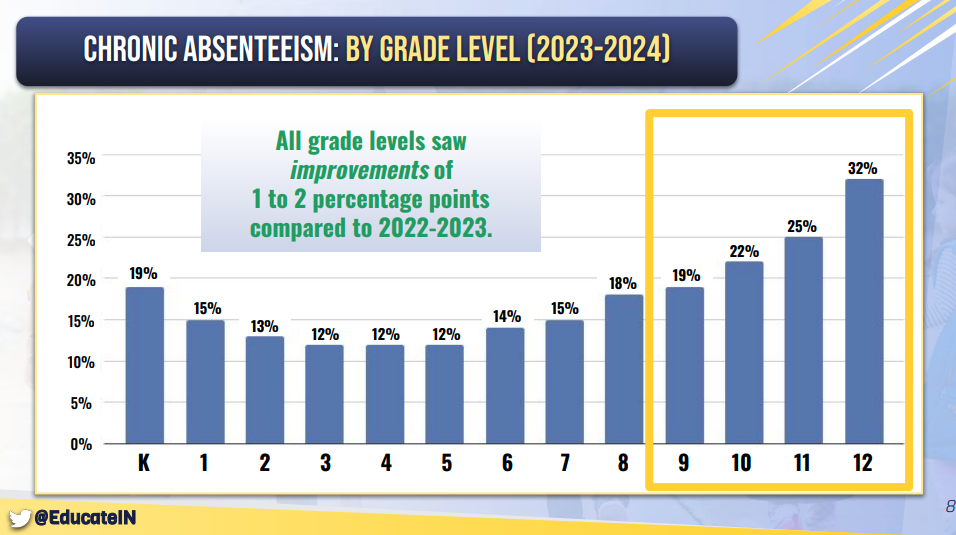

Chronic absenteeism rates in Indiana are on the decline . . . but hundreds of thousands of students are still missing school on a regular basis – a problem exacerbated by the pandemic. We told you in our last issue that during the 2023-24 school year, 17.8% of students were chronically absent, down from 19.2% in the previous year. This improvement follows a peak of 21.1% during the pandemic in 2022.

That percentage shakes out to about 205,000 students who were chronically absent last year, or enough to fill 2,805 school buses.

In the eyes of the State Board of Education, who were shown the data on Wednesday, the dashboard may be a gamechanger for schools trying to discern the “why” behind chronic absenteeism.

Board member Pat Mapes calls the spread of accessible data on the dashboard “unbelievable,” emphasizing that it’s critical for the state to show the difference being present in school can make on academic achievement. He notes while educators have long expressed this fact without this data before them, he doesn’t know if parents have been able to see that, and this is a way to show them.

“Parents have to understand that your kids in our buildings is how they can progress academically and build the skills they need to be successful,” Mapes observes. He points out, “We’ve really never had anything like this to be able to pull data out to really make that story.”

Poor attendance affects academic performance across all grade levels, and that’s clear comparing assessment scores between students who are chronically absent, and those who are not.

Only 67.2% of chronically absent students passed the IREAD-3 exam in 2024, while 84.2% of students who were not chronically absent passed. Similar trends are also seen in ILEARN and SAT scores, with the difference in the latter being the starkest.

Indiana’s SAT passing rate among 2024 graduates was generally poor for a number of other factors, but of the chronically absent high school students who took the test, just 17.5% met the college-ready benchmark. For non-chronically absent students, 41.1% met that benchmark.

“The magnitude of that is startling,” Secretary of Education Katie Jenner observes. “If you look at the inverted bell curve, we look at the high schools, which is certainly the most significant, but if you look at kindergarten and first grade that is a lot higher than it should be. That’s when our teachers are working on the foundations with kids.”

So, how will this data help as the state continues to try to find solutions to bring down chronic absenteeism? The idea is to present this data so schools can pinpoint where problem areas are – because ultimately, state officials see the issue primarily being resolved at the local level.

“What we’re doing is holding up the mirror on this attendance data and allowing schools to slice it any way they can possibly think of,” explains John Keller, chief information officer for IDOE.

The dashboard shows several years worth of week-by-week attendance data on excused and unexcused absences, and rates of chronic absenteeism and habitual truancy. On the school-access dashboard, data will be updated in real-time for schools to filter through. The public dashboard won’t be updated as regularly, as IDOE will only post certified data when it’s released in bulk yearly.

Districts can use the real-time data on their dashboard versions to quickly evaluate whether policies aimed to improve attendance are actually helping.

Schools can take that data, for example, and dig into whether there are repeating patterns, such how many consecutive years a student has been chronically absent. There could be one particular week one year where a lot of students missed school . . . and that district can use the dashboard data to pull those numbers and determine any common factors among students who missed school at that time.

Educators around the state have been grappling with pinpointing the reasons to why students are missing school. The answer is complex because, as your favorite education newsletter has detailed over several issues, each district’s students face different challenges. Those could range from family challenges at home to newer tendencies to keep children home when they feel sick . . . and sometimes wait days to get into to see a doctor.

Keep in mind, too, that chronic absenteeism is different than being a habitutal truant – which is prosecutable under Indiana law. Habitual truancy means a student has 10 or more unexcused abscesses within one school year, while chronic absenteeism is defined as missing at least 10% of the school year, or about 18 days. Those 18 days count for excused and unexcused absences.

Rather than just pushing local prosectors to take on truancy cases, schools have to get creative on solutions to chronic absenteeism.

Schools are coming up with solutions locally. For example, the small Medora Community School Corporation recently launched a a virtual in-school urgent care service called Nurses Direct Connect. This service provides real-time access to healthcare for students, helping to reduce absences due to mild illnesses. The service is free for schools and ensures that students

can receive care without needing to leave school, making it easier for families to manage health issues without disrupting their schedules.

With that, is chronic absenteeism solely on the state to solve? How much time should IDOE and state lawmakers spend on new policy? That’s difficult to answer.

Lawmakers certainly saw how daunting of a task it was to try to legislate ways to make kids go to school, and had to trim down the one truancy law passed in the 2024 session to just address K-6 grades. That law only addresses truancy, requiring elementary schools to intervene earlier if students miss so many days of school without an excuse. The issue of chronic absenteeism was then kicked to a summer study committee (which we’re still awaiting the first meeting of this interim).

State education officials are thinking more big picture. Giving schools this data is one way of being part of the solution. Dr. Keller explains the state is shifting its tfocus from “just a school-focused look at attendance” to honing in on individual students.

IDOE generally in the last few years has been collecting a swath of data sets from schools and placing the information on real-time dashboards. The last dashboard launched earlier this year tracking data on the state’s reading profiency rates.

Dr. Jenner on Wednesday also mentioned the idea of creating a state goal for attendance rates, such as setting a goal to return back to pre-pandemic levels of absenteeism within five years after 2025. Still, that’s not a goal IDOE can simply set and hope to achieve on its own, she notes.

“We are on that trajectory,” Dr. Jenner observes. “The department would be willing to lean with some associations to set a state goal.” She adds, “I just think rather than the State Board of Ed or the department doing it, just us, we’d much rather see us come together and say ‘we’re all in this to get kids to school.’ ”

Up next, you can expect IDOE to lean in on the attendance dashboard and the data when presenting proposals for legislation for next year.

Dr. Jenner has been in conversations about the absenteeism issue with lawmakers on the Interim Study Committee on Education tasked with study it ahead of the committee’s first meeting expected in the coming weeks . . . though she didn’t divulge much detail on what she wants to see emerge from that panel in terms of future legislation.

“The first step as a state is we have to make sure we’re honest and transparent about our data,” Dr. Jenner asserts. “Let’s invest in what’s working, so being able to lay out that exactly what our data looks like for parents and families, school leaders, teachers, community leaders to all have access to – that’s where the conversation starts.”

You may also want to bear in mind that when the study topic was assigned, we also heard from legslative leaders who want to not “over-legislate” the issue. Leaders last fall also said they would tackle absenteeism more in the 2024 session, but then the issue was absent from the legislative priorities in the House and Senate. With all of that in mind, what exactly will come from the study committee, if anything, remains to be seen.